Professional beauty vlogger broadcasting cosmetic makeup tutorial on social media

Getty

Digital marketers have to deploy AI. They also have to defeat it

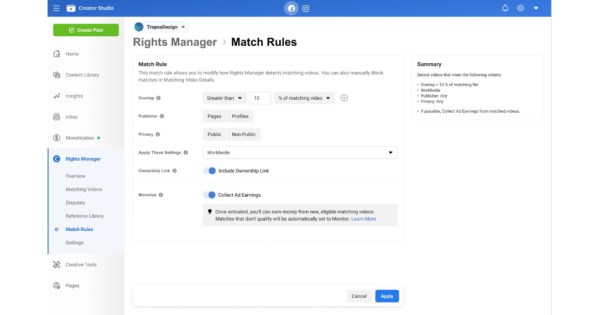

In October 2017, Facebook altered the Instagram API to make it harder for users to search its giant database of photos. The change was a small element of the company’s response to the Cambridge Analytica scandal, but it was a significant problem for parts of the digital marketing industry.

Not long before, New York-based influencer marketing agency Amra & Elma had developed a platform that ingested data from Instagram, and allowed its client to use AI image classifiers to find very specific influencers. For instance, they could find an influencer with, say, between 10,000 and 50,000 followers who had posted photos of themselves in a Jeep. Facebook’s move killed this capability in a keystroke. Another day in the digital duel between the AIs deployed by digital marketers, and those deployed by the social media platforms.

Analytics is all

Once upon a time, successful advertising was a question of artistic creativity and financial muscle. Hire a hot agency to produce a 30-second ad, spend a lot of money with TV and newspaper owners, and you were bound to make a splash. The Mad Men of Madison Avenue were about sizzle and silver, not science.

The internet has changed all that. Today it is all about data, analytics, and algorithms. Google and Facebook have made off with much of Rupert Murdoch’s ad revenue, by the simple method of making adspend accountable, and much, much more targeted. With Google Ads you only pay when a consumer clicks on your ad. With Facebook ads you know far more about the type of people your ads are being served to. It is no longer “spray and pray”.

Digital marketing is now the sexy part of the advertising industry, and its currency is data. The ability to obtain and analyse data is the core skill, not a good line in patter and a generous expense account. It is more important to understand the mechanics of the social media platforms than to know the maitre d’ at the latest trendy restaurant.

Elma Beganovich, co-founder of Amra & Elma, says “AI is a game changer in digital marketing, especially influencer marketing. Brands are now able to pinpoint their target demographic precisely, and speak to them directly. Technologies like voice recognition allow us to identify what topics influencers are talking about on YouTube and Instagram TV.”

Influencer marketing is a significant and fast-growing section of the digital marketing industry. The big agency networks (WPP, Omnicom, Publicis, and Interpublic) have their players, and there are hundreds of independent outfits. The industry is currently valued at $8bn, and before COVID-19 came along, was forecast to double in the next two years. Jessy Grossman, founder of Women In Influencer Marketing (WIIM), thinks that the virus might accelerate growth: “Brands have been hit hard. We are going to see them pinch every penny and demand the most ROI. Digital marketing is far more efficient, data driven and quick. It’s also the most economical way to get production quality content and large-scale distribution at a fraction of the price.”

Data tames the Wild West

In its early days, when Instagram was new, influencer marketing was a lawless, wild west environment – the least data-driven part of the digital marketing industry. Clients were eager to benefit from the adulation that influencers can inspire, but they had no way to measure the return on their investment, and unscrupulous influencers were buying fake followers by the thousand.

But analytics are taking over, even here. Clients want to know what they are getting for their money, and consumers want to know when they are receiving sponsored messages. Analytics are critical in understanding the level of engagement between influencers and their followers. And regulators have corralled influencers into using hashtags to indicate when a post has been paid for.

Influencer marketing is still mainly a B2C (business to consumer) activity, with the big three client categories being beauty, food, and fashion. But B2B (business to business) usage is taking off too, with influencers becoming important in financial services, pharmaceuticals, and technology.

The big money still goes to TV celebrities and footballers, with hundreds of millions of Instagram followers – Kylie Jenner charges $1m for a single post. But as the industry matures, it is finding roles for more modest players, and a hierarchy has evolved. Macro influencers have more than half a million followers, the mid-tier has 100,000 plus, the micro influencers have 10,000 plus, and last but not least are the nano influencers, with 1,000 to 10,000 followers. Clients can bundle influencers with more modest followings, allowing more precisely targeted marketing. And influencers with smaller followings often generate more engagement with, and attention from, their followers.

Platform evolution

Influencer marketing has been around in various forms for centuries, and its monetisation gathered pace with the rise of reality TV shows in the noughties. But it was the arrival of social media platforms which made it an industry. These platforms are evolving fast; they wield great power, but they are always at risk of being superseded by the latest trend. Millennials declined to use the platform favoured by their parents, so Facebook acquired Instagram in 2012 for $1bn (and WhatsApp in 2014 for $19bn). SnapChat refused to be acquired by Facebook, but Zuckerberg managed to overtake it by making Instagram Stories more user-friendly.

Alongside Instagram, YouTube is the other great influencer platform. Videos allow YouTubers to form more emotional bonds with their audiences. Facebook launched Instagram TV (IGTV) in June 2018, but so far it has failed to repeat the success against Google-owned YouTube that Instagram Stories achieved against Snapchat.

The new kid on the block is TikTok. Jessy Grossman says, “TikTok is all that everyone is talking about. The virality of it is like YouTube years ago. While it seems to attract a young audience, I’ve also seen all kinds of content perform well on there. The tools it provides its users directly in the platform are fairly complex, and really encourage interesting content.”

Clients, agencies and the influencers themselves are engaged in a constant battle with the platforms. They desperately want to maximise the attention secured by their posts, and they are constantly innovating, and refining their techniques, to raise their ranking on the platforms. The platforms, on the other hand, want great content to keep their audiences engaged, but if anyone is going to pay to promote a piece of content, they want it to be their own ads, not an agency. Artificial intelligence is the most powerful weapon in both sides’ armouries.

Darwin plus data

The platforms actively court the influencers, and welcome the highly curated and creative content they produce. They use machine learning and other AI techniques to help influencers raise their game still further. But they also deploy AI, and continually evolve their algorithms, to prevent influencers and agencies from gaming the system using their own data and AIs. It is a constant struggle: Darwin plus data.

AI is also helping the agencies manage the bewildering growth in the number of influencers. OMD and GroupM, the media agencies of the ad networks Omnicom and WPP, both launched AI tools in early 2018 to match influencers to brands, and assess the performance of campaigns they run together.

Virtual influencers

Influencers are often accused of being fake: fake followers, fake tans, fake lifestyles. A single photo can take a day to set up, with an army of stylists and make-up artists as well as the photographer and the lighting team. And then there is the photoshop team.

As well as working hard to get the right image, influencers have to strike the right tone. Quite a few of them have struggled with this since the murder of George Floyd and the return of the black Lives Matter movement. Influencers have been harshly criticised for using protest events as a backdrop for a fashion-related shoot. But even before the pandemic, the fakery went to an extreme: meet the virtual influencers.

Lil Miquela is a freckly Brazilian 19 year-old who lives in Los Angeles. 80,000 people stream her songs on Spotify each month, and she counts Prada among her clients. She has 2.2m followers on Instagram, and many of them know that she is entirely fictional. She was created in 2016 by Brud, a startup in LA which specialises in CGI, artificial intelligence, and robotics. Until 2018, Brud allowed Lil’s followers to believe she was real, and then they staged her “kidnap”, using another avatar, called Bermuda. A Trump-supporting “robot supremacist”, Bermuda accused Lil of being a “fake ass person” and said she could not have her account back until she told the world the truth. Brud is now said to be worth $125m.

The virtual influencer story took another turn after the virus lockdown, when the WHO contracted with Influential, another LA-based studio, to obtain the services of Knox Frost, a CGI rendering of a 20 year-old from Atlanta, with a million followers on Instagram. Frost posts about the need to observe the lockdown, and to wash hands frequently. Elma Beganovich of Amra & Elma claims these virtual influencers are not a fad, but “a genuine game-changer, with millions and followers and A-list clients.”

Like the rest of digital marketing, influencers – and the agencies which monetise them – are here to stay. The constant sparring of their AIs, their algorithms and their data, with those of the social media platforms, will continue to improve their effectiveness and their efficiency.